Although it’s not uncommon for the penis to curve slightly when it’s erect, a more significant bend may be a symptom of Peyronie’s disease. It’s no longer considered to be an uncommon or rare problem as more and more men are desperate to communicate or share their concerns with their clinicians, if not their family and friends.

So it’s time we dealt with it more openly, just as we did with erectile dysfunction (ED) over the last two decades.

What is Peyronie’s disease?

Peyronie’s disease (PD) is the commonest cause of bent penis and, although known to medicine for over 250 years ago, the underlying cause is not yet understood. As a consequence, treatments have been directed towards treating the symptoms rather than the cause.

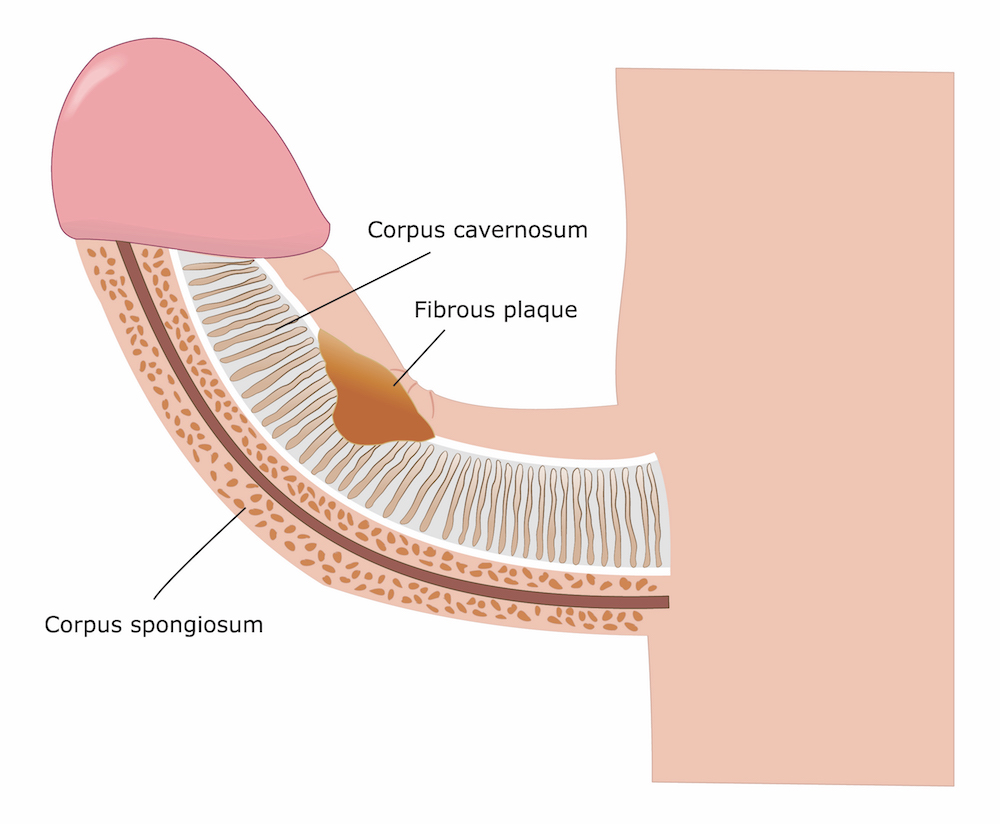

PD is a collagen disorder that is characterised by scar tissue, called plaques, that form under the skin. These plaques can cause the penis to bend during erections (although curvature is the most common ‘deformity’, others include indentation, hourglass narrowing, loss of girth and penis shrinkage/shortening):

The resulting curvature may make penetrative sex difficult or painful to the patient and/or his partner, causing additional physical/psychological distress and difficulties in the relationship. ED may set in due to pain/deformity/distress.

Most men with PD present with it in their mid-fifties without any previous injury/event to account for it. Pain present in the initial stage resolves with time in >90% of cases. The penile curvature is progressive in 30-50% of men and stabilises in 47-67% with a hard/calcified plaque.1,2

PD can be associated in some cases with co-existent Dupuytren’s contracture (DC; bent fingers) or Ledderhose scarring of plantar fascia (bent toes). 9-39% men with PD reported co-existent DC, whereas 4% of men with DC also had PD. Other associated risk factors are diabetes, hypertension, ischaemic cardiopathy, smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, ED and dyslipidaemia – although their contributions to the condition are unclear.

Why does PD develop?

Minor injury

The most widely accepted hypothesis is that PD develops after an injury to the penis when erect, such as being bent during vigorous sex. Injury to the tunica albuginea, a collagen tissue layer within the penis, may cause scar tissue to form in the collagen coating (fibrosis). This scar tissue then forms the plaques of PD.

Genetic predisposition

Some researches think that there may be genetic reasons for why PD plaques form. However, PD is different to ‘congenital penile curvature (CPC)’ where men are born with curvature of the penis (noticeable as soon as young men become sexually active); PD is an ‘acquired’ condition not ‘congenital’.

How common is PD?

Prevalence of PD varies widely from 0.5-20% in the literature, making it a significant patient burden on any health care system.3

However, this could just be the tip of the iceberg, as most men tend to shy away from approaching their doctor due to embarrassment. It is therefore crucial that clinicians probe into this issue when assessing men presenting with ED and/or lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), as they can co-exist with PD.

The personal impact of PD

PD is known to have physical and psychological impact, with a high incidence of clinical depression in those affected. Up to half of men with PD admit to it having an adverse impact on their relationship, never mind the negative impact on their masculine image and quality of sex life.

They tend to suffer silently, and so do their partners.

Stages of PD

Men with PD first go through an ‘active/acute’ phase; this is characterised by dynamic and changing symptoms, in particular penile pain and deformity on erection which leads to increasing distress. Erections may or may not be compromised.

The condition then enters its ‘stable/chronic’ phase, with symptoms remaining unchanged for 3-6 months. In this phase the pain may subside but deformity/curvature and plaque remain.

In 3-15% of men, the disease process is known to resolve spontaneously over 6-12 months, particularly in younger men.1,2,4

How to manage PD

The focus of treatment is on symptom control rather than disease cure. After a clinical diagnosis of PD, supported by an ultrasound scan (USS) or MRI if necessary, the active phase is best managed by masterly inactivity or doing very little actively, to allow the condition to take its course until the process is stabilised or resolved.

During this phase what the patient really needs most is:

- Reassurance

- Counseling

- Baseline assessment of disease/deformity including distress scores for PD, VAS (Visual Analogue Score) for pain and PDQ (Peyronie’s Disease-specific Questionnaire)

- Detailed discussion of treatment options and their risks/benefits

- Setting goals of treatment for the patient/clinician

- Setting realistic expectations for the patient/clinician

- Shared decision making between the patient and clinician

Treatment options for the active phase

During the active phase, men with PD may be offered NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) for symptomatic relief of their pain.

For all other oral agents and intra-lesional agents described in the literature (see below), there is no convincing evidence of any lasting benefit; with none getting “A” grade recommendation based on the level of evidence; as such none should be offered without appropriate prior counseling about their limited potential for success. These agents fall into three types:

- Oral agents:g. vitamin E, potaba, tamoxifen, PDE5i (Viagra [sildenafil], Cialis [tadalafil]) colchicine, carnitine, pentoxifylline

- Intra-lesional agents: e.g. verapamil, interferon a2b, steroids

- Topical treatments: e.g. verapamil, iontophoresis

Mechanical/physical therapies may also be used and include the use of Extracorporeal Shock Wave Treatment (ESWT), traction device and vacuum device.

Treatment options for the stable phase

In men with stable deformity without ED, further management depends upon following issues:

- Impact on self image

- Difficulty with sex

- Psychological distress

- Effect on relationship

- Expectations from the chosen treatment option

The clinician ought to have a frank discussion about the options available based on the extent of deformity/angulation, and with realistic expectations set out for what the treatment can offer.

Options include:

- Surgical correction: penile shortening (plication techniques)

- Surgical correction: penile lengthening (incision/grafting technique) +/- penile prosthesis

- Intra-lesional injection using verapamil/interferon a-2b

- No treatment for minor deformity without any compromise of sexual function (for angulations <30 degrees)

The new kid on the block…

Xiapex® (EU) or Xiaflex® (US) is an intra-lesional agent (collagenase clostridium histolyticum) recently licensed for managing PD. It is the only drug approved by the FDA in the US for the treatment of PD. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has not approved any drug for the treatment of PD at this point in time.

Xiapex® is an outpatient-based, minimally-invasive, non-surgical treatment option. It is administered as a course of up to eight injections over a period of 24 weeks depending upon the degree of curvature and response to treatment.

In clinical trials, a reduction in the curvature of up to 17 degrees (37%) was noted at the 1-year follow up.

Although it is not the panacea of treatment for PD, it is most certainly a significant addition to the armamentarium for the management of PD; the evidence for most of the existing options being at best moderate to conditional.

In summary…

If a man has developed a curved/bent penis, he should be made aware that he is not the only one out there with one.

There are presently several options at the clinician’s disposal that can be used to address this condition in a bespoke manner according to the extent of deformity.

It is time men stopped suffering in silence, came out in the open and become actively involved in making a shared decision with their clinician about their choice of treatment.